were euthanizing an estimated 15 million homeless animals a year. In the 1960s, shelters and animal control agencies in the U.S.

These pet service deserts have a broader impact as well. When their kids’ cat develops a hacking cough, how can they get her to a doctor when they have no car, and their friends have no cars, and the nearest vet is 10 miles away, and would charge them the amount they need to feed the family that week? If their beloved dog plays too rough, what can they do when there’s no behaviorist nearby and when paying for training would mean not paying the heating bill? That has enormous consequences for people and their pets. Most people are aware of how “food deserts”-areas where affordable and nutritious food is hard to access-impact the lives of working poor families, but those food deserts often coincide with a lack of other services, including veterinary clinics and other pet needs. Through their work with the HSUS Pets for Life (PFL) program, Huston, Schipkowski and Mutch are part of a movement of people around the country who are working to close those distances. People just across the street can seem like they’re miles away. Details like that can get lost at a distance. So it’s no wonder that Ross’s neighbor, looking across at the group, didn’t notice the specifics of the logos on the jackets-on Schipkowski and Mutch, silhouettes of animals forming the outline of the United States on Huston, a cat, a dog, a heart. Or someone in some other official capacity that’s likely to mean one thing: Your day-maybe your whole life-is about to get worse. Or they may be utility reps planning to turn off your water. In this mostly black part of Detroit, when a group of mostly white people wearing black windbreakers with logos shows up outside your house, they’re probably police. It’s an unsettling remark, and a reminder of the realities in the neighborhoods where Huston works, which are poor, isolated from services and largely racially segregated. He approaches, smiling tentatively, and makes his hesitation clear: “I thought you might be the cops.” Photo by M. He stays there for several minutes until Ross and Schipkowski wave him over. Through the outreach work conducted by her organization, she helped get both dogs neutered and vaccinated, and they seem to regard her as a visiting aunt.īut the rest of the group are newcomers on the block, and across the street, one of Ross’s neighbors comes onto his porch to give them a onceover. Huston has known Ross and his dogs for years now. “I wouldn’t have named him that myself,” Ross says, shaking his head. Diablo, he explains, was a name the dog got from his previous owner.

Huston digs in her trunk for a new rawhide while Ross stands by, smiling down at his pooch. He’s clearly aware of what Huston’s car signifies: treats. Diablo, a big white pit-bull-type, bounds around delightedly and, once off his tether, plants himself expectantly in the middle of the group, his tongue lolling out as he glances from face to face expectantly. His two dogs are tethered in the yard, the worn patches outside their wooden doghouses overflowing with warm straw bedding. Huston pulls up at a house and steps out to greet Jerome Ross, a tall, middle-aged man who’s come outside to meet them. Now and then, there’s a burnt-out shell, the blackened beams and collapsed walls standing in spiky piles between empty homes and others that are proudly occupied, where lights are on and chairs sit on front porches and small, pristine gardens display their early buds next to streets cluttered with trash.

The wave of fires peaked in the 1980s, but still, every day in Detroit, more houses burn than the police can investigate.ĭriving through the neighborhood, Huston passes many abandoned houses-windows broken, shingles scattered in the front yard leaving bald patches on the roofs. But as Detroit’s automobile industry crumbled and a huge chunk of the population moved away, the city began to suffer from the impact of that plunging economy and tax base. It started as mostly pranks, kids acting up and causing only minor destruction. Since the 1930s, the night before Halloween has been known in the city as Devil’s Night. It’s hard to tell where the smell’s coming from, but Detroit is famous for its fires.

#Kindred the family soul surrender to love zip windows#

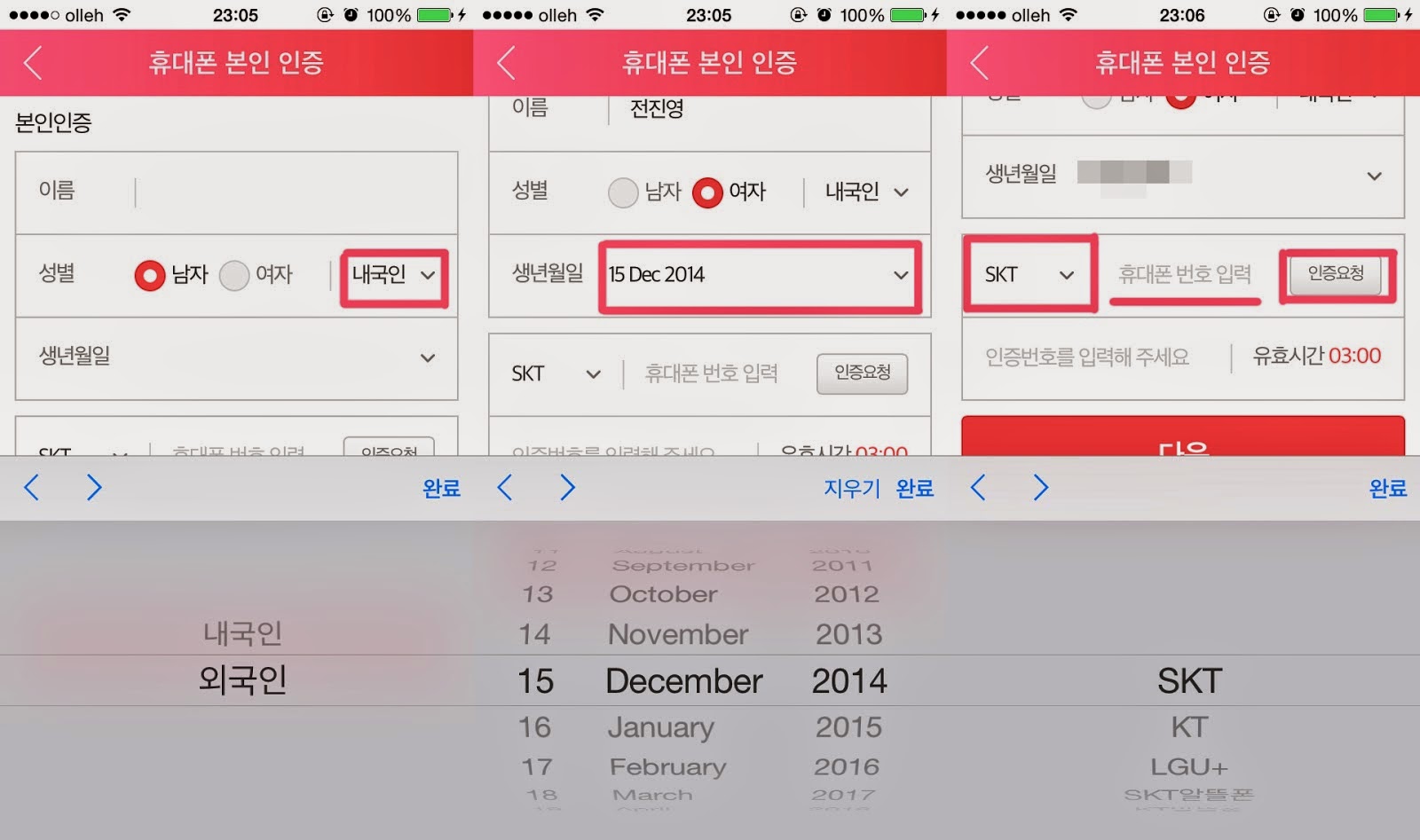

Even with the windows rolled up-it’s early spring, but a thin sleet is falling-they can smell it: plastics, wood, a taint of smoke. In the back seat, HSUS staffers Jason Schipkowski and Ashley Mutch sniff the air. "There’s another house burning,” Kristen Huston says, steering her white sedan, the trunk loaded with pet supplies, into one of the Detroit neighborhoods where her organization, All About Animals Rescue, does outreach. Driving change In Detroit and underserved neighborhoods around the country, Pets for Life is bridging gapsĪnimal Sheltering magazine September/October 2016 Photo by Bryan Mitchell/AP Images for the HSUS

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)